When he returned to active practice he saw at once that the courts had grown more learned and dignified and that the bar relied more upon method and system and a knowledge of the statute law than upon the stump speech method of early days.

Mr. Herndon tells us that Lincoln would lie in bed and read by candle light, sometimes until two o'clock in the morning, while his famous colleagues, Davis, Logan, Swett, Edwards and Herndon, were soundly and sometimes loudly sleeping. He read and reread the statutes and books of practice, devoured Shakespeare, who was always a favorite of his, and studied Euclid so diligently that he could easily demonstrate all the propositions contained in the six books.

Mr. Lincoln detested office work. He left all that to his partner. He disliked to draw up legal papers or to write letters. The firm of which he was a member kept no books. When either Lincoln or Herndon received a fee they divided the money then and there. If his partner were not in the office at the time Mr. Lincoln would wrap up half of the fee in a sheet of paper, on which he would write, "Herndon's half," giving the name of the case, and place it in his partner's desk.

But in court, arguing a case, pleading to the jury and laying down the law, Lincoln was in his element. Even when he had a weak case he was a strong antagonist, and when he had right and justice on his side, as he nearly always had, no one could beat him.

He liked an outdoor life, hence he was fond of riding the circuit. He enjoyed the company of other men, liked discussion and argument, loved to tell stories and to hear them, laughing as heartily at his own stories as he did at those that were told to him.

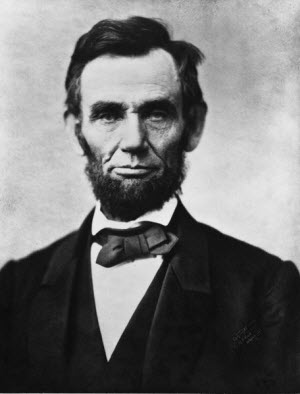

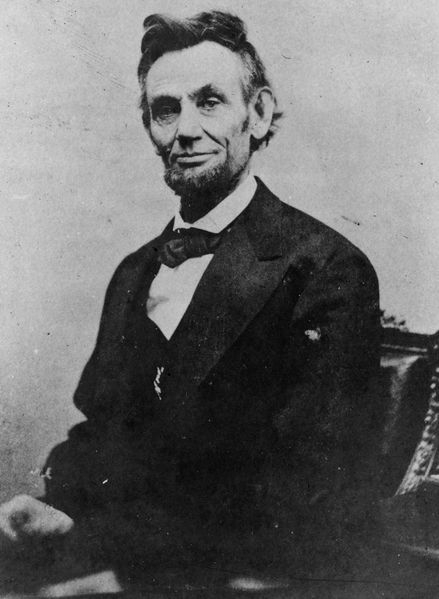

Abraham Lincoln | Events | People | Abraham Lincoln Quotes |

Quotations About Abraham Lincoln | Abraham Lincoln Photo Gallery | Abraham Lincoln Timeline |

Privacy Policy | About Us | Site News | Site Map |

Anecdotes and Stories About Abraham Lincoln