A FUN-LOVING AND HUMOR-LOVING MAN.

It was once said of Shakespeare that the great mind that conceived the tragedies of "Hamlet," "Macbeth," etc., would have lost its reason if it had not found vent in the sparkling humor of such comedies as "The Merry Wives of Windsor" and "The Comedy of Errors."

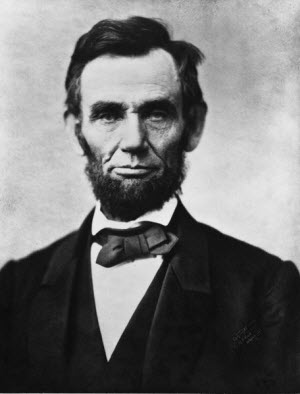

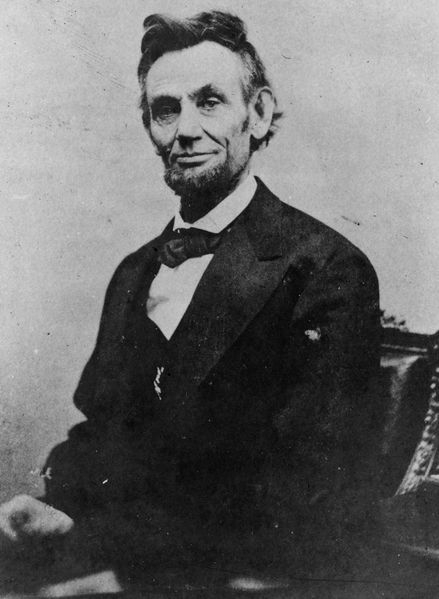

The great strain on the mind of Abraham Lincoln produced by four years of civil war might likewise have overcome his reason had it not found vent in the yarns and stories he constantly told. No more fun-loving or humor-loving man than Abraham Lincoln ever lived. He enjoyed a joke even when it was on himself, and probably, while he got his greatest enjoyment from telling stories, he had a keen appreciation of the humor in those that were told him.

His favorite humorous writer was David R. Locke, better known as "Petroleum V. Nasby," whose political satires were quite famous in their day. Nearly every prominent man who has written his recollections of Lincoln has told how the President, in the middle of a conversation on some serious subject, would suddenly stop and ask his hearer if he ever read the Nasby letters.

Then he would take from his desk a pamphlet containing the letters and proceed to read them, laughing heartily at all the good points they contained. There is probably no better evidence of Mr. Lincoln's love of humor and appreciation of it than his letter to Nasby, in which he said: "For the ability to write these things I would gladly trade places with you."

Mr. Lincoln was re-elected President in 1864. His opponent on the Democratic ticket was General George B. McClellan, whose command of the Army of the Potomac had been so unsatisfactory at the beginning of the war. Mr. Lincoln's election was almost unanimous, as McClellan carried but three States--Delaware, Kentucky and New Jersey.

General Grant, in a telegram of congratulation, said that it was "a victory worth more to the country than a battle won."

The war was fast drawing to a close. The black war clouds were breaking and rolling away. Sherman had made his famous march to the sea. Through swamp and ravine, Grant was rapidly tightening the lines around Richmond. Thomas had won his title of the "Rock of Chickamauga." Sheridan had won his spurs as the great modern cavalry commander, and had cleaned out the Shenandoah Valley. Sherman was coming back from his famous march to join Grant at Richmond.

The Confederacy was without a navy. The Kearsarge had sunk the Alabama, and Farragut had fought and won the famous victory in Mobile Bay. It was certain that Lee would soon have to evacuate Richmond only to fall into the hands of Grant.

Lincoln saw the dawn of peace. When he came to deliver his second inaugural address, it contained no note of victory, no exultation over a fallen foe. On the contrary, it breathed the spirit of brotherly love and of prayer for an early peace: "With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation's wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphans, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations."

Not long thereafter, General Lee evacuated Richmond with about half of his original army, closely pursued by Grant. The boys in blue overtook their brothers in gray at Appomattox Court House, and there, beneath the warm rays of an April sun, the great Confederate general made his final surrender. The war was over, the American flag was floated over all the territory of the United States, and peace was now a reality. Mr. Lincoln visited Richmond and the final scenes of the war and then returned to Washington to carry out his announced plan of "binding up the nation's wounds."

He had now reached the climax of his career and touched the highest point of his greatness. His great task was over, and the heavy burden that had so long worn upon his heart was lifted.

While the whole nation was rejoicing over the return of peace, the Saviour of the Union was stricken down by the hand of an assassin.

Abraham Lincoln | Events | People | Abraham Lincoln Quotes |

Quotations About Abraham Lincoln | Abraham Lincoln Photo Gallery | Abraham Lincoln Timeline |

Privacy Policy | About Us | Site News | Site Map |

Anecdotes and Stories About Abraham Lincoln