President Lincoln, while entertaining a few friends, is said to have related the following anecdote of a man who knew too much:

During the administration of President Jackson there was a singular young gentleman employed in the Public Postoffice in Washington.

His name was G.; he was from Tennessee, the son of a widow, a neighbor of the President, on which account the old hero had a kind feeling for him, and always got him out of difficulties with some of the higher officials, to whom his singular interference was distasteful.

Among other things, it is said of him that while employed in the General Postoffice, on one occasion he had to copy a letter to Major H., a high official, in answer to an application made by an old gentleman in Virginia or Pennsylvania, for the establishment of a new postoffice.

The writer of the letter said the application could not be granted, in consequence of the applicant's "proximity" to another office.

When the letter came into G.'s hand to copy, being a great stickler for plainness, he altered "proximity" to "nearness to."

Major H. observed it, and asked G. why he altered his letter.

"Why," replied G., "because I don't think the man would understand what you mean by proximity."

"Well," said Major H., "try him; put in the 'proximity' again."

In a few days a letter was received from the applicant, in which he very indignantly said that his father had fought for liberty in the second war for independence, and he should like to have the name of the scoundrel who brought the charge of proximity or anything else wrong against him.

"There," said G., "did I not say so?"

G. carried his improvements so far that Mr. Berry, the Postmaster-General, said to him: "I don't want you any longer; you know too much."

Poor G. went out, but his old friend got him another place.

This time G.'s ideas underwent a change. He was one day very busy writing, when a stranger called in and asked him where the Patent Office was.

"I don't know," said G.

"Can you tell me where the Treasury Department is?" said the stranger.

"No," said G.

"Nor the President's house?"

"No."

The stranger finally asked him if he knew where the Capitol was.

"No," replied G.

"Do you live in Washington, sir."

"Yes, sir," said G.

"Good Lord! and don't you know where the Patent Office, Treasury, President's House and Capitol are?"

"Stranger," said G., "I was turned out of the postoffice for knowing too much. I don't mean to offend in that way again.

"I am paid for keeping this book.

"I believe I know that much; but if you find me knowing anything more you may take my head."

"Good morning," said the stranger.

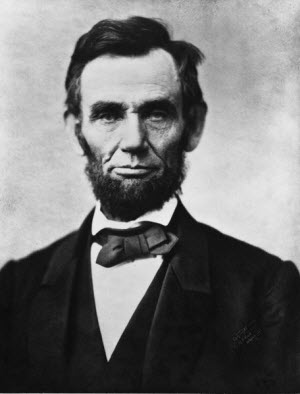

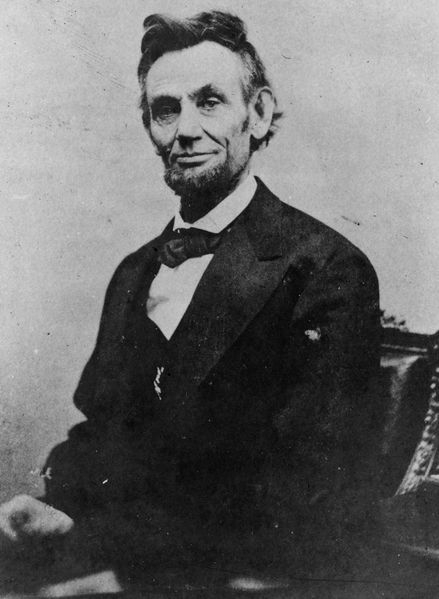

Abraham Lincoln | Events | People | Abraham Lincoln Quotes |

Quotations About Abraham Lincoln | Abraham Lincoln Photo Gallery | Abraham Lincoln Timeline |

Privacy Policy | About Us | Site News | Site Map |

Anecdotes and Stories About Abraham Lincoln