Lincoln delivered a remarkable speech at Springfield, Illinois, when but twenty-eight years of age, upon the liberty possessed by the people of the United States.

In part, he said:

"In the great journal of things happening under the sun, we, the American people, find our account running under date of the nineteenth century of the Christian era.

"We find ourselves in the peaceful possession of the fairest portion of the earth as regards extent of territory, fertility of soil, and salubrity of climate.

"We find ourselves under the government of a system of political institutions conducing more essentially to the ends of civil and religious liberty than any of which history of former times tells us.

"We, when mounting the stage of existence, found ourselves the legal inheritors of these fundamental blessings.

"We toiled not in the acquisition or establishment of them; they are a legacy bequeathed to us by a once hardy, brave, and patriotic, but now lamented and departed race of ancestors.

"Theirs was the task (and nobly did they perform it) to possess themselves, us, of this goodly land, to uprear upon its hills and valleys a political edifice of liberty and equal rights; 'tis ours to transmit these--the former unprofaned by the foot of an intruder, the latter undecayed by the lapse of time and untorn by usurpation--to the generation that fate shall permit the world to know.

"This task, gratitude to our fathers, justice to ourselves, duty to posterity--all imperatively require us faithfully to perform.

"How, then, shall we perform it? At what point shall we expect the approach of danger?

"Shall we expect some trans-Atlantic military giant to step the ocean and crush us at a blow?

"Never! All the armies of Europe, Asia and Africa, combined, with all the treasures of the earth (our own excepted) in their military chest, with a Bonaparte for a commander, could not, by force, take a drink from the Ohio, or make a track on the Blue Ridge, in a trial of a thousand years.

"At what point, then, is this approach of danger to be expected?

"I answer, if ever it reach us, it must spring up amongst us. It cannot come from abroad.

"If destruction be our lot, we must ourselves be its author and finisher.

"As a nation of freemen, we must live through all time or die by suicide.

"I hope I am not over-wary; but, if I am not, there is even now something of ill-omen amongst us.

"I mean the increasing disregard for law which pervades the country, the disposition to substitute the wild and furious passions in lieu of the sober judgment of courts, and the worse than savage mobs for the executive ministers of justice.

"This disposition is awfully fearful in any community, and that it now exists in ours, though grating to our feelings to admit it, it would be a violation of truth and an insult to deny.

"Accounts of outrages committed by mobs form the every-day news of the times.

"They have pervaded the country from New England to Louisiana; they are neither peculiar to the eternal snows of the former, nor the burning sun of the latter.

"They are not the creatures of climate, neither are they confined to the slave-holding or non-slave-holding States.

"Alike they spring up among the pleasure-hunting Southerners and the order-loving citizens of the land of steady habits.

"Whatever, then, their cause may be, it is common to the whole country.

"Many great and good men, sufficiently qualified for any task they may undertake, may ever be found, whose ambition would aspire to nothing beyond a seat in Congress, a gubernatorial or Presidential chair; but such belong not to the family of the lion, or the tribe of the eagle.

"What! Think you these places would satisfy an Alexander, a Caesar, or a Napoleon? Never!

"Towering genius disdains a beaten path. It seeks regions hitherto unexplored.

"It seeks no distinction in adding story to story upon the monuments of fame, erected to the memory of others.

"It denies that it is glory enough to serve under any chief.

"It scorns to tread in the footpaths of any predecessor, however illustrious.

"It thirsts and burns for distinction, and, if possible, it will have it, whether at the expense of emancipating the slaves or enslaving freemen.

"Another reason which once was, but which to the same extent is now no more, has done much in maintaining our institutions thus far.

"I mean the powerful influence which the interesting scenes of the Revolution had upon the passions of the people, as distinguished from their judgment.

"But these histories are gone. They can be read no more forever. They were a fortress of strength.

"But what the invading foeman could never do, the silent artillery of time has done, the levelling of the walls.

"They were a forest of giant oaks, but the all-resisting hurricane swept over them and left only here and there a lone trunk, despoiled of its verdure, shorn of its foliage, unshading and unshaded, to murmur in a few more gentle breezes and to combat with its mutilated limbs a few more rude storms, then to sink and be no more.

"They were the pillars of the temple of liberty, and now that they have crumbled away, that temple must fall, unless we, the descendants, supply the places with pillars hewn from the same solid quarry of sober reason.

"Passion has helped us, but can do so no more. It will in future be our enemy.

"Reason--cold, calculating, unimpassioned reason--must furnish all the materials for our support and defense.

"Let those materials be molded into general intelligence, sound morality, and, in particular, a reverence for the Constitution and the laws; and then our country shall continue to improve, and our nation, revering his name, and permitting no hostile foot to pass or desecrate his resting-place, shall be the first to hear the last trump that shall awaken our Washington.

"Upon these let the proud fabric of freedom rest as the rock of its basis, and as truly as has been said of the only greater institution, 'the gates of hell shall not prevail against it.'"

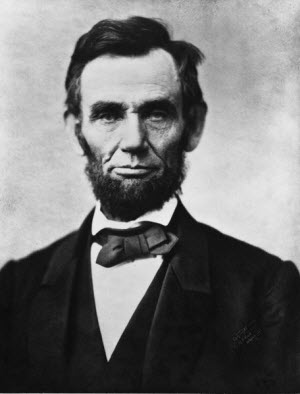

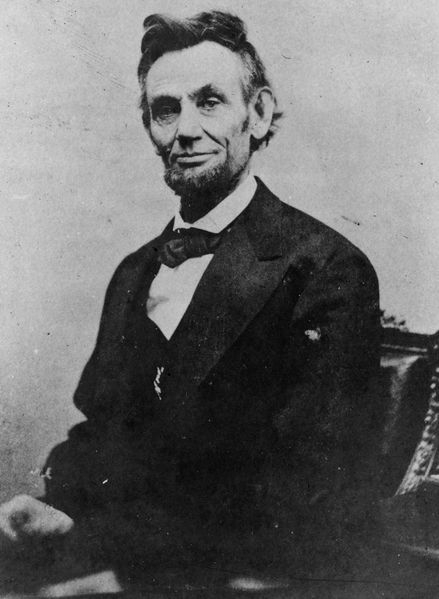

Abraham Lincoln | Events | People | Abraham Lincoln Quotes |

Quotations About Abraham Lincoln | Abraham Lincoln Photo Gallery | Abraham Lincoln Timeline |

Privacy Policy | About Us | Site News | Site Map |

Anecdotes and Stories About Abraham Lincoln